Read PART 1 HERE first 🙂

Then there’s the story of exponential transformation, which seems for the moment to be secluded to political talks without much substantial policy carrying it, while not being strongly and commonly carried ahead by the scientific community and civil society. Christiana Figueres, former executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, used this framing at the Global Climate Action Summit. “I’m going to tell you a story. A story of a journey that we’re already on. A story about exponential transformation.”

She referred the exponential trend to the growth of solar and wind power, green bonds, electric vehicles, divestment and carbon pricing in terms of countries participating and coverage of the global greenhouse gas emissions. She was speaking the voice of pathos, while sustainability scientist Johan Rockström with whom she was on stage the one of logos. They thus combined their appeal to emotions and reason, and there was no need to convince the audience of their credibility as speakers. Just for that bit of history, logos – ethos – pathos are the three main forms of rhetoric according to Aristotle.

This can definitely be a strong story, but I had to ask myself: First, is this really a story of transformation and was cherry-picking of sectors justifiable? Figueres actually addressed the second question herself in the talk but didn’t answer it. And second: is this the story that matters?

A roadmap where to?

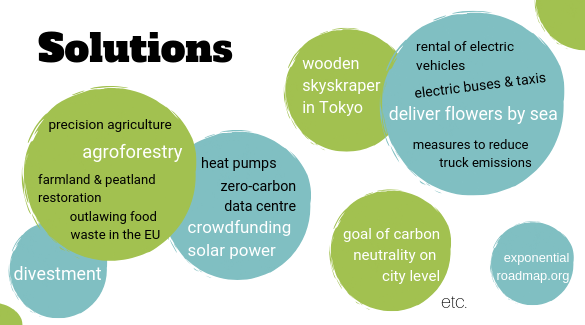

The exponential climate action roadmap, which maps out 30 solutions to halve emissions by 2030 across all sectors, was the basis to the talk. The roadmap clearly says that the Paris Agreement’s goal to reduce the risk of dangerous climate change can be achieved if greenhouse gas emissions peak by 2020, halve by 2030 and then halve again by 2040 and 2050. We’re far away from that for now. To me the solutions proposed as best practices seemed more of a collection without connections in between and without asking the question: what is really the impact of every single one of them. But I might be wrong.

->The Story of Stuff initiative uses the acronym GOAL to define transformational solutions in its video The Story of Solutions. A real solution gives people more power, opens people’s eyes to the truth of happiness as coming from well-being and not consumption, accounts for all the costs and lessens the wealth gap. More info here and in the script. If we take this definition of solutions then only few of the single best-practices named in for example the Exponential Climate Action Roadmap presented at the Global Climate Action Summit can be considered as such.

->In community building, and the loose worldwide community of climate action advocates around the world, sharing stories or experiences “can build trust, cultivates norms, transfers tacit knowledge, facilitates unlearning, and generates emotional connections”. Concretely, we can all try to encourage and look out for a big story of change as the Figueres example and small, individual stories. As someone telling a story it helps to keep in mind the purpose of the telling, since a story could be too vivid and seductive for the recipient – a friend, or a decision-maker – to critically evaluate its meaning for their own work while taking it in. It’s also best to tell the story from several points if view to be credible or to put it differently, give a second story to judge from.

Local storytelling and national narratives

Thelma Young, 350.org Digital Storyteller and Social Media Manager, put its clearly: “For too long the stories of climate change have been dominated by journalists, celebrities, politicians and scientists from predominantly European and North American countries. And while it’s good that Leonardo DiCaprio is using his status to create a climate documentary, the truth is — we need to go beyond this and build up new regional networks of climate storytellers.” Yes, and at the same time I don’t know enough of the world’s climate storytellers to assess the situation. All I know, is that even in Europe we need more stories of people affected by climate change on this continent and stories show-casing best-practices. In Europe, even inside the EU, it’s easy to forget that we have different histories and national narratives that are more or less conducive to change in the face of climate change. Stories, a platform for them, are even if nothing more a necessary part that supports societal change and the sense for a common endeavour.

Just to get back to national narratives for a moment. Take the example of Sweden that developed its “Swedish model” of economy from the 1930s to the 1980s based on a notion of equality between people and social justice. Adding to this the traditions of prioritizing education, using science in policymaking, people’s closeness to natural resources and the importance of local governments explain how the country could quickly adopt technology of biomass fuel to replace fossil fuels. To make technological transformation possible on a national level, people making a change often try to “connect a new story to powerful national narratives in such a way that the new technology becomes part of the story of who the nation is.”

U.S-American journalist Robinson Meyer covering climate change made a point that is valid for all of the Global North and that stuck with me in its simplicity. That is that in preferring to see ourselves as truly innocent we use climate storytelling to reassure us of that and point the finger at oil companies and the like as culprits, because they are outside the narrative we are trying to protect. This we also call othering. Another point he makes is that a misunderstanding of storytelling is a focus on sea level rise or melting ice, giving a false sense of local impacts being most severe in restricted regions affected by that.

(c) Adi Goldstein on Unsplash

As I figured before, no one here on this planet has THE answer to how to tell stories on climate change. Maybe as Meyer writes, “the more interesting narrative forms are likely to background climate change and make it appear like the theater in which human dramas are unfolding.” Compare that to the 19th and 20th century, where stories were set against the backgrounds of industrial revolution and wars. Just that in this century climate change is the dominant background instead.

Literature and journalism are closer than we think, TV is different

Often we refer to stories, thinking for example of breaking news, when we actually mean information. “Literature tells stories. Television gives information.” These are the words of Susan Sontag, U.S.-American writer, filmmaker, philosopher, teacher, and political activist. And personally, I support that view. The idea of an endless flow of information that is all “potentially relevant” or so-called interesting is opposed to paying attention to a story and reducing the simultaneity of everything; because “to tell a story is to say: this is the important story.” Sontag argues that a reality of non-stopped stories creates a detachment that is anti-ethical as compared to a novel or unarguably in-depth journalism. She also writes that literature is imperfect knowledge, just like all knowledge.

In the words of the U.S.-novelist Ursula K. Le Guin, storytelling can offer an imaginative but persuasive alternative reality. This is the basis to break our mind’s habit that the present way of doing things is the only way. If we think about it, we need both journalism and fantasy to imagine a different world and often the two are closer than we think.

In a world in which objectivity is touted as the number one goal of journalism that wants to be taken seriously I want to make the point that this objectivity is in fact unattainable, which is by no way a reason to despair. Instead, journalism and literary forms are intertwined and can learn from each other on the power of words. This doesn’t mean journalism can somehow take its moral-ethical responsibility less seriously and NOT do everything to get the facts right.

“Serious fiction writers think about moral problems practically. They tell stories. They narrate. They evoke our common humanity in narratives with which we can identify, even though the lives may be remote from our own. They stimulate our imagination. The stories they tell enlarge and complicate — and, therefore, improve — our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” – Susan Sontag, here

And if the capacity of paying attention is the basis for moral judgement then how can we as journalists and everyone of us contribute to that in a world of information overflow and short attention spans?

We can re-imagine change

The Center for Story-Based Strategy, a national strategy centre dedicated to help social justice networks and organizations use the power of narrative for social change, created a book that can’t be missed here. It’s called Re:imagining change – How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world. Well, pretty ambitious and definitely inspiring.

The book introduces the concept of control mythologies that shape a shared sense of political reality, normalize the status quo, and obscure alternative options or visions. It also presents us with the narrative power analysis to understand the story we are trying to change, identify the underlying assumptions that allow that story to operate as truth and find the points of intervention in the story where we can challenge, change and/or insert a new story. And last but not least, we get to know memes. No, not those funny images with text layered on top, but any unit of culture that spreads beyond its creator. This could be a buzz word, catchy melody, fashion trend, idea, ritual, image, some “contagious information patterns” 😉 Put differently, memes are condensed ideas that are ideologically based.

As you guessed, there’s lots of control memes out there that have the function of tilting the popular perception towards supporting the current situation (status quo). These memes include too big to fail (referring to banks), free trade, clean coal, the war on […] or jobs vs the environment. More concretely, a black American was described in the U.S. media as “looting” a supermarket after hurricane Katrina, while a white man just “found” the food. A positive meme would be for example Billionaires for Bush OR Gore, a widely adopted street theatre meme that transmitted the message that big money owned both presidential candidates.

And in our context? Critical mass, the worldwide movement in which bikers (or also inline skaters and others) gather and make their way through a city together is a meme. These memes have been successful because of being flexible and adaptive to local conditions. Brainstorming further, I could think of hackathons or cloth swap parties as other examples.

“Expanding the frame of the picture reframes the entire story and changes our understanding of who has the power.”

The book provides much more info on how to use concepts of storytelling to create a successful campaign.

Turning to practice, where can a new story intervene? In short, at points of production like a factory, destruction such as a waste disposal site, consumption – here leading to memes like “sweat-shop free” and “fairtrade”-, points of decision unmasking hidden interests or challenging assumptions of who is to blame for a story as well as at points of assumption. The last one is no physical point in contrast to others, but no less impactful. Actually, it makes all the difference, since assumptions are the glue that holds a narrative together. And it can happen in various ways, by:

- Offering new futures: This happens through countering the TINA (There is no alternative myth). It’s neighbourhood farming lots countering corporate take-over of the food system. It’s stories that open up the political imagination to the possibility of a real solution.

- Reframing the debate: Here it’s actions foreshadowing a different ending to the story, as in the example of an action of the movement Earth First! In which, in 1981, they unfurled a huge banner showing a crack running all the height of a contested dam. It created a new political space, foreshadowing a day of restored rivers and removed dams.

- Subverting the spectacle: In our context it’s for example a direct action by activists at an official event of the state, a company or local authority.

- Repurposing pop cultural narratives: Just let me quote the banner: “Frodo has failed – Bush has the ring!”, in 2003. Here it’s important to understand whether your target group is familiar with a specific pop cultural code like the one above.

- And making the invisible visible: Coming again from the U.S. perspective of the book, Iraq Veterans Against the War initiated an action to change the story from WAR to OCCUPATION. By what means did they do that? They gave the public the experience of what occupation is through reality street theatre set in iconic places, which created a cognitive dissonance – a mental discomfort.

The Greenpeace Save the Whale campaign in the 70s is such an intervention at a point of assumption that inspired many environmental campaigns they way that is common today. Since the NGO couldn’t ever have intervened at every point of destruction to save every whale, they “set out to change the way the dominant culture thought of whaling – to change the story of whaling”. Pictures showed Greenpeace activists in small boats putting themselves between whales and whaling ships and established the new narrative of the giant whaling ships being the monsters, not the whales.

Why storytelling matters in science and research

It’s quite valid to say that a human story is a nice thing but won’t convince decision makers or climate deniers or let’s say climate sceptics to change their mind and act. The story of a risky scientific expedition into the ice of Greenland shows that a good story can also be a scientific story, because it focused on the process in a descriptive and visual way and not the end result.

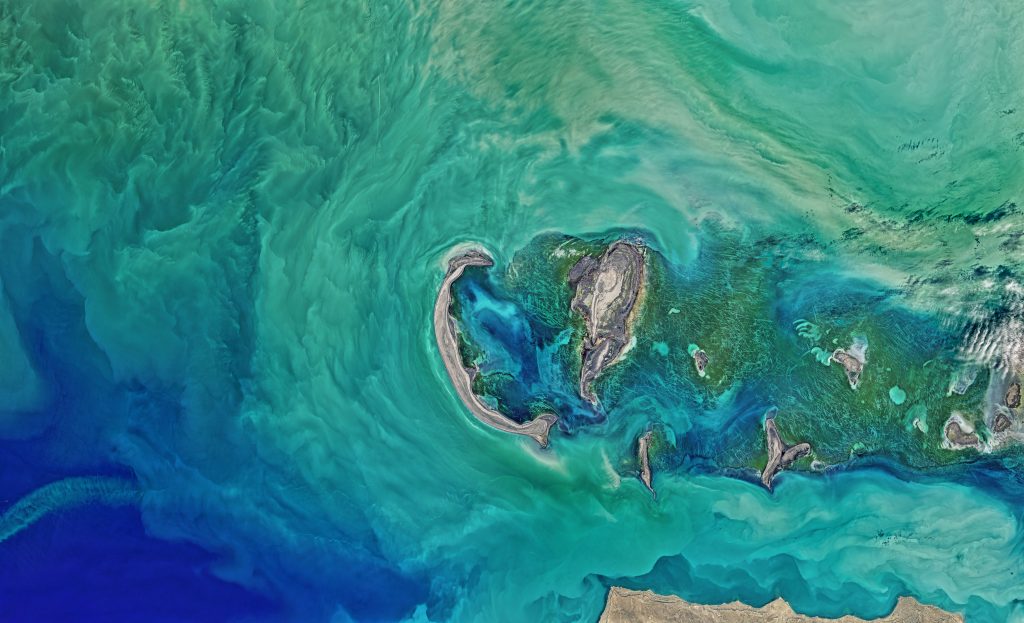

The intersections between the art of writing and art of doing science are huge, as pointed out by a science communicator at NASA. “Science, including the type of satellite remote sensing at which NASA excels, is based on making detailed observations and allowing those observations to tell their story.” Stories are also increasingly accepted as data sources in energy and climate change research. But why? Because they might “offer a way to surface insights, misconceptions, beliefs, experiences, or perspectives that commonly exist but are not systematically brought to light” as a study shows.

Stories can be success stories, “learning stories” (what happens in practice) and “caring stories” (what needs to happen over time) in energy or anything from news coverage of extreme weather events to traditional weather-knowledge systems among Maori on climate change.

Stories are usually local and can also help to improve interventions by collecting more complete user experiences rather than making assumptions instead. They allow to look at processes that create circumstances such as fuel poverty, not just at the situation, the end-result itself. Stories can be without words, but this is a whole different, large topic. Moving away from research for second, the way of council and specific forms like the Talanoa dialogue in climate politics use the method of sitting in a circle as immediate form of telling stories.

The analysed stories of climate refugees distance, victimize, disempower; at the same time, stories can also repair the dignity of a speaker. Stories include the “known, but under-acknowledged” which is very hard through the usual, quantitative data collection. And while stories could still be categorized better, using stories to frame the problem of energy demand “could contribute to a wider set of ‘solutions’”. Stories can lead to more solutions, that’s it. Stories are used to zoom in, zoom out, zoom through. What for? In the bigger picture to see forgotten possibilities and assumptions and visions, in the smaller picture the “why”s and “what”s and by zooming through to critically analyse stories to uncover cultural assumptions, framings and the like. “Stories become clues as to where to look.”

Storytelling on climate change should not provide more data but address the underlying political reasons for not talking action. The fear of losing jobs, stalling national economies and sacrificing opportunity.

How to storytell

There are very different ways to tell a story, but here are some points to help you on your way to your own story:

- Start your story with a complication that requires a decision of the character or you, or start it before; In any case, create an image from the start, and a protagonist who is relatable and has a goal or mission.

- If you need to, stop and break an image you had just created for the audience and show a different aspect instead, or a different ending to the story.

- Ask people to “imagine…” or “suspend disbelief” for a moment.

- Keep up the pace in the beginning of the story and follow the structure, use words like “therefore” and “but” as a glue for the story.

- Let a moment of realization and true transformation be the climax of your story.

- Find personal stories whatever you are writing about and start with your own story. Think about failures, obstacles, lucky breaks, and epiphanies in your life to tell them and deliver a message.

- Leave space for the audience to fill in the gaps, let them create their story in their mind, because this is what sticks and engages people

- An open ending can inspire action.

- Positive stories matter.

- Stories are not always in words – wherever you can “show, don’t tell”

- Wherever you smell a story think: Am I asking the right questions? They are important.

- Play with your perspectives and experiment with narratives.

- Remember the power of questions, not finished answers.

- Meet your audience where they are, not where you want them to be.

- Remember that people won’t listen to a story that contradicts their core beliefs, as much in love as you may be with that story yourself.

- When building a counter-narrative DON’T use the keywords of the narrative you want to demolish (failure of political left in that).

Some more tips here and more on digital climate storytelling in this deck of cards by 350.org. Also, Working Narratives works with communities to tell great stories that inspire, activate and enliven democracy and has a useful strategy guide for storytelling and social change online.

A good story is a surprising rollercoaster and brings responsibility

Studies from cognitive theory in global change offer some more insight into what makes a good story. Maybe you think it’s obvious anyway, but a series of isolated facts or details do not create meaning. A fascinating text with lots of interesting but irrelevant details will diminish its power. When a story is interesting instead, the information from it is integrated with the readers‘ existing knowledge to form a map, or model, of the story. “A good story is incorporated into the pre-existing cognitive structures representing what the reader already knows.”

Also, if most events in a story are causally related, we will remember the story more easily. Making a goal state or end point clear to the reader throughout the text helps to create a coherent story; so here we go again, it’s all about the narrative arc – a beginning, a middle, an end. And a tinge of mystery, just think of your favourite novel or film.

And a bit of surprise. A tip on storytelling I encountered is to take the audience on a journey with many twists and turns and confuse them. Get them wondering out loud what the hell is going to happen next. Exactly, even when you set out to explain something. Then the listener or reader can put the pieces of the story together themselves and own the story a little.

To pick up a word of caution expressed in the study: stories are great if used with caution especially concerning historical analogies and when used as guides for action, not probabilistic forecasts. As we discussed in the storytelling course, good stories avoid generalizations such as “the media”. Replacing a stereotype with another is not going to make a change and I’m convinced we can instead all help each other recognize if ever such new stereotypes come up. Equally, it helps to keep an explanatory and not persuasive stance when talking about solutions, which means adopting a different vocabulary like state instead of government.

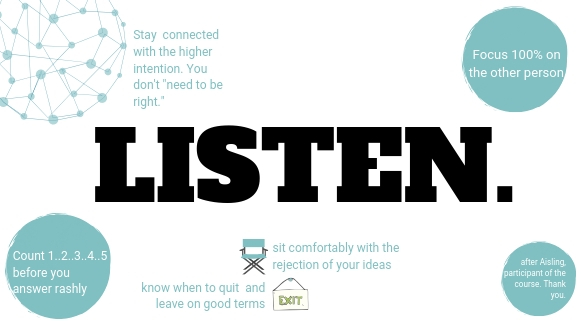

How to start a conversation on climate change

Just start with a question like Do you have a few minutes now? Or Can I talk to you about something? Most importantly: LISTEN. I know myself that I would itch to interrupt, but don’t. If the person doesn’t talk much, then learn something about them through personal questions like What have you heard about climate change? How do you feel about that? No need to go into science here. Then repeat and reflect their words to let know that you are LISTENING through a sentence like What I’m hearing you say is that.., is that right?” or “That’s a good point. I never thought of that.” Then you can start your story: “Can I tell you what I’ve been thinking about?” Talk and then ask what the other person thinks of it. In short, have a conversation.

Challenge facts and ideas, not the people. – Carmine Rodi Falanga, trainer at the storytelling course

Sometimes the other person won’t take seriously what you are trying to say. Here comes some advice: “Rather than banging your head against a locked front door by starting out talking about global warming, use a side door, such as talking about the multiple benefits of clean energy, like jobs and economic growth.”

Back to the future

Coming back to the beginning, I left the storytelling course with a baggage of thoughts, dreams, stories, ideas and friends. And many, many critical questions. I also took with me the answer, or an answer, to what makes a message effective after watching a video in the group. It’s keywords, repetition, authenticity, clarity, examples that leave no room for confusion, numbers showing scale, humour, a simple structure, comparisons. A message is not a story, but you might want to look for messages conveyed by stories around you or get that message out in your next conversation in the bar. And since we’re talking about messages: a powerful message is “how can we help”, not “how we can stop doing harm”.

I am concerned about the focus put on energy transition in the discourse about climate action, even if it’s the one BIG transformation that needs to happen now. More practically, sustainable communities and urban innovations are not all about solar panels. We can all stop and think: how can I contribute to a more sustainable and happy community in the place I’m in?

I share Carl Sagan’s vision of a society capable of both critical thinking and kindness. He realized that both scepticism and wonder are skills that need practice, which will require huge changes in education to be achieved. He envisioned a journalism open to every notion, dismissing nothing but for a good reason but demanding stringent standards of evidence. We all love stories, but this doesn’t mean we have to believe them blindly. This will help you uncover faulty arguments a story can be based on.

Maybe you have noticed that this text referenced several U.S.-based authors. This is frankly a coincidence but also shows that there are no borders to serious research and powerful stories. This was just an excurse, quite possibly flawed, and quite certainly subjective and incomplete, into the wide expanse of a topic that encompasses everything. Please just keep learning.

Source of cover picture: Stergo on Pixabay

(c) of all the graphics: klimareporter.in